If Kelso's choice to depict Amberlight as the precise reversal of many restrictive patriarchal societies is unimaginative, she is at least to be commended for committing to it whole-heartedly.

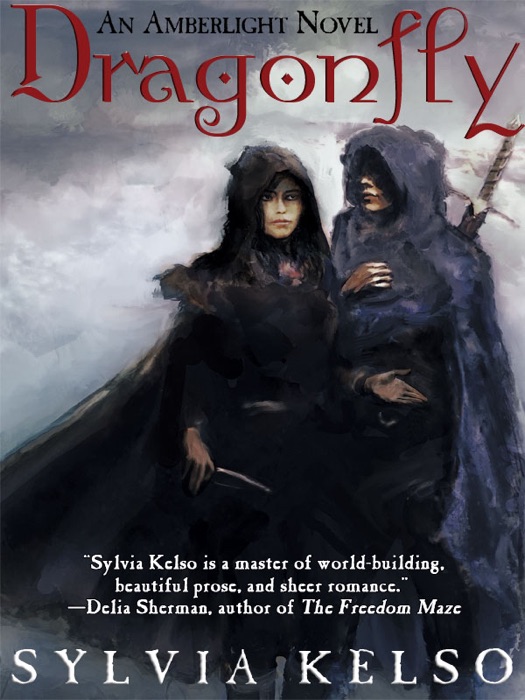

Men are relegated to the roles of breeders and playmates, and in high-ranking families such as Tellurith's are housed in their own, proscribed quarters where they spend their days making themselves beautiful and practicing the art of being engaging, accommodating companions. Kelso's interest seems to have been mainly in establishing Amberlight as a vital and influential player in its local web of power, and in this respect, as in many others, she leaves the world outside the city lightly sketched.) Qherrique can only be mined by women, who as a result have assumed complete control of Amberlight's politics and professions. (Just how this effect manifests itself, especially in a world in which every major ruler has a statuette, is never sufficiently explained. To outsiders its significance is in the statuettes Amberlight sells to foreign rulers, who use them to influence and control their subjects and enemies. Part stone, part living matter, and perhaps even sentient, qherrique is used to power Amberlight, heat and cool its houses, and drive its weapons and tools. Perhaps inevitably, she doesn't hit, but she does achieve the somewhat dubious distinction of falling into both of these common fallacies, one after the other.Īmberlight is told from the perspective of Tellurith, chief of one of the ruling families in the titular city, whose wealth and power are derived from a substance called qherrique. In her 2007 novel Amberlight and its 2009 sequel Riversend, Sylvia Kelso, a scholar of both feminism and science fiction, takes another stab at this elusive target. To assume that women are paragons of virtue is to forget that women are people, and to assume that women are flawed in exactly the same way as men is to unthinkingly accept that "people" means the same thing as "men." Steeped as we are in patriarchal concepts and power structures, it seems to stretch the powers of the imagination to their breaking point to envision the form those power structures might take if women were at society's reins. Neither approach is particularly satisfying, nor, to my mind, particularly feminist. For all the pride of place that unbridled speculation and the meticulous construction of alternate worlds have within these genres, when it comes to imagining a female-led society authors seem to fall, again and again, into the same traps, depicting such societies as either utopias in which aggression and injustice are defeated by women's naturally compassionate and cooperative nature, or mirror images of patriarchal societies in which gender roles are identical to the ones we know but have been inhabited in the opposite order. Despite numerous attempts over the years, imagining a matriarchal society seems to have presented a particular challenge to science fiction and fantasy writers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)